Clarity over caution: how to write a better intended purpose for SaMD

Clear, testable, objective intended-purpose statements make compliance, evidence generation, and clinical adoption much simpler.

Manufacturers too often try to play it safe with the wording for their intended purpose: the classic “this product does not replace clinical judgement” line, hedged user groups, or blanket caveats. Those vague phrases don’t buy you safety, they make your regulatory life harder.

Why objectivity is optimal

- Vague or caveated statements force regulators (and you) to assume the broadest possible use and population, which increases the evidence and risk burden.

- Disclaimers like “not a substitute for clinical judgement” don’t change the device’s function or risk profile — they’re words, not a substitute for clinical evidence or design controls. Regulators care about what the software does, who uses it, and how its outputs are intended to act in a clinical pathway.

What to aim for

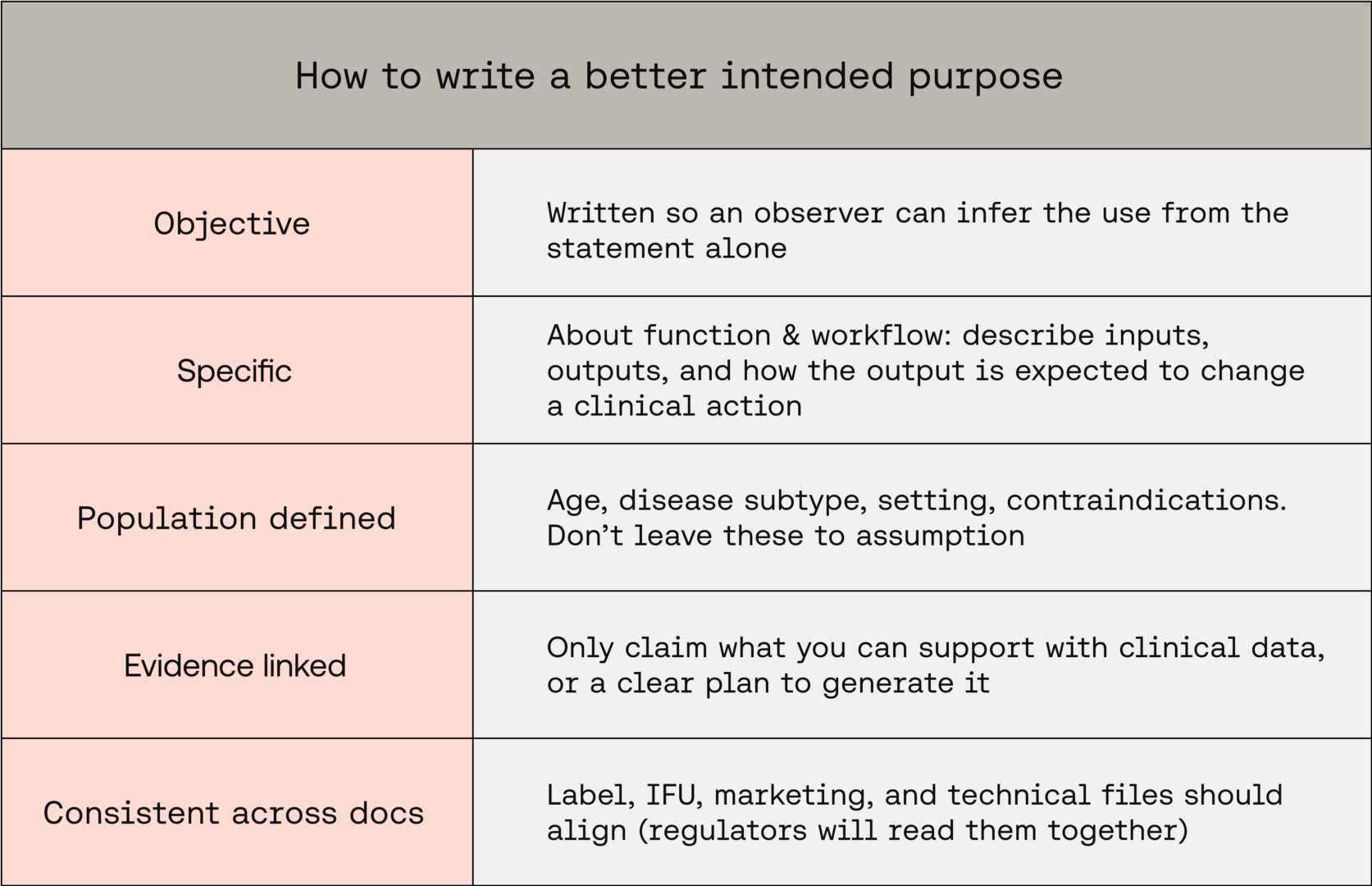

When you craft an intended purpose, align it to the following:

These principles align with the MHRA’s practical method for building intended-purpose statements and with international SaMD thinking from IMDRF.

A concrete example

Before (defensive, vague):

“This tool assists clinicians in assessing patient risk and should be used alongside clinical judgement. Not for paediatric use.”

Problems:

- “assists” is ambiguous (what does it do?)

- “assessment of patient risk” has no population detail

- the “alongside clinical judgement” line is a non-specific disclaimer that doesn’t define intended influence on decisions

After (objective, testable):

“For use by emergency department physicians to identify adults (≥18 years) with suspected acute pulmonary embolism. The software analyses chest CT angiography images and produces a binary ‘high/low probability’ output to prioritise cases for review; it is intended to support triage decisions in ED workflow and has been validated on adults 18–85 years with contrast-enhanced CT. Contraindicated for paediatric patients and non-contrast CTs.”

Why this is better:

- It states user, use environment, input, exact output, intended action, and constraints - all of which are testable and map to evidence needs.

Other regulators agree

The FDA’s Clinical Decision Support (CDS) and digital-health clarifications show regulators focus on function and intended use, not on comfort-wording. If the software meets device definitions, a disclaimer won’t remove oversight. (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, HHS.gov)

IMDRF and recent MDCG work are the global reference points for SaMD definition, risk categorisation, and software classification. Use those frameworks when thinking about how broad or narrow your purpose should be. (imdrf.org, Public Health)

Key takeaways

- Remove guarded statements — make the statement factual, not apologetic

- Specify user, input, output, intended use-action, population, and constraints

- If you can’t support a claim with evidence, don’t put it in the intended purpose

Short, objective intended purposes save time, reduce regulatory friction, and make your clinical-evidence plan clearer. Draft them as statements of fact — not hedged legalese.

Want Scarlet news in your inbox?

Sign up to receive updates from Scarlet, including our newsletter containing blog posts sent straight to you by email.