How to avoid common pitfalls for SaMD clinical State of the Art

When it comes to establishing the clinical State of the Art for SaMD and AI medical devices, there are important considerations to ensure your submission is comprehensive, balanced, and reflective of the current medical landscape. But what are the common pitfalls to this? And why do they matter?

What makes a comprehensive clinical SotA?

Establishing the clinical State of the Art (SotA) provides the baseline for understanding the current medical knowledge, clinical practices, accepted endpoints, and alternative methods relevant to your SaMD. It sets the scene for your clinical evaluation and performance claims and helps define the clinical benefit and acceptability of any residual risks. This is not necessarily the latest or most cutting-edge practices, but rather what is clinically accepted in the medical field.

According to EU MDR Annex XIV, the clinical evaluation must consider “the current knowledge/state of the art in the corresponding medical field.” This is not limited to what’s been published in peer-reviewed journals but also includes broader sources of information that reflect the real-world clinical environment your device intends to operate in.

Sources for building a clinical SotA

Both published and non-published data can contribute valuable information towards a robust clinical SotA. These may be identified through a variety of tools, including but not limited to:

1. Literature searches

As per MEDDEV 2.7/1 rev. 4 and EU MDR requirements, a structured literature search is essential to identify data on:

- Current and alternative methods used to diagnose, monitor, or treat the condition in question

- Epidemiological and demographic data on the target patient population

- Established clinical practices and clinical endpoints

- Safety and performance data of comparable or legacy devices

- Limitations and gaps in existing technologies

- Standards and clinical guidelines that define “acceptable” performance or safety

Take, for example, a smartphone-based blood pressure monitoring app: literature searches should retrieve studies, reviews, guidelines covering digital monitors, home-use monitoring, clinical outcome measures (e.g. systolic/diastolic accuracy), and usability factors that might impact users.

2. Grey literature searches and online sources

Clinical SotA isn’t solely rooted in peer-reviewed literature. Grey literature and non-published data sources — like clinical practice guidelines, health technology assessments (HTAs), professional society white papers, and regulatory safety alerts — offer valuable insight into evolving standards, off-label uses, or real-world user behaviour.

Sources may include:

- WHO and NICE guidelines

- FDA and MDCG publications

- Professional society position statements (e.g., ESH/ESC guidelines for hypertension)

- Market surveillance data

- Conference abstracts or expert consensus documents

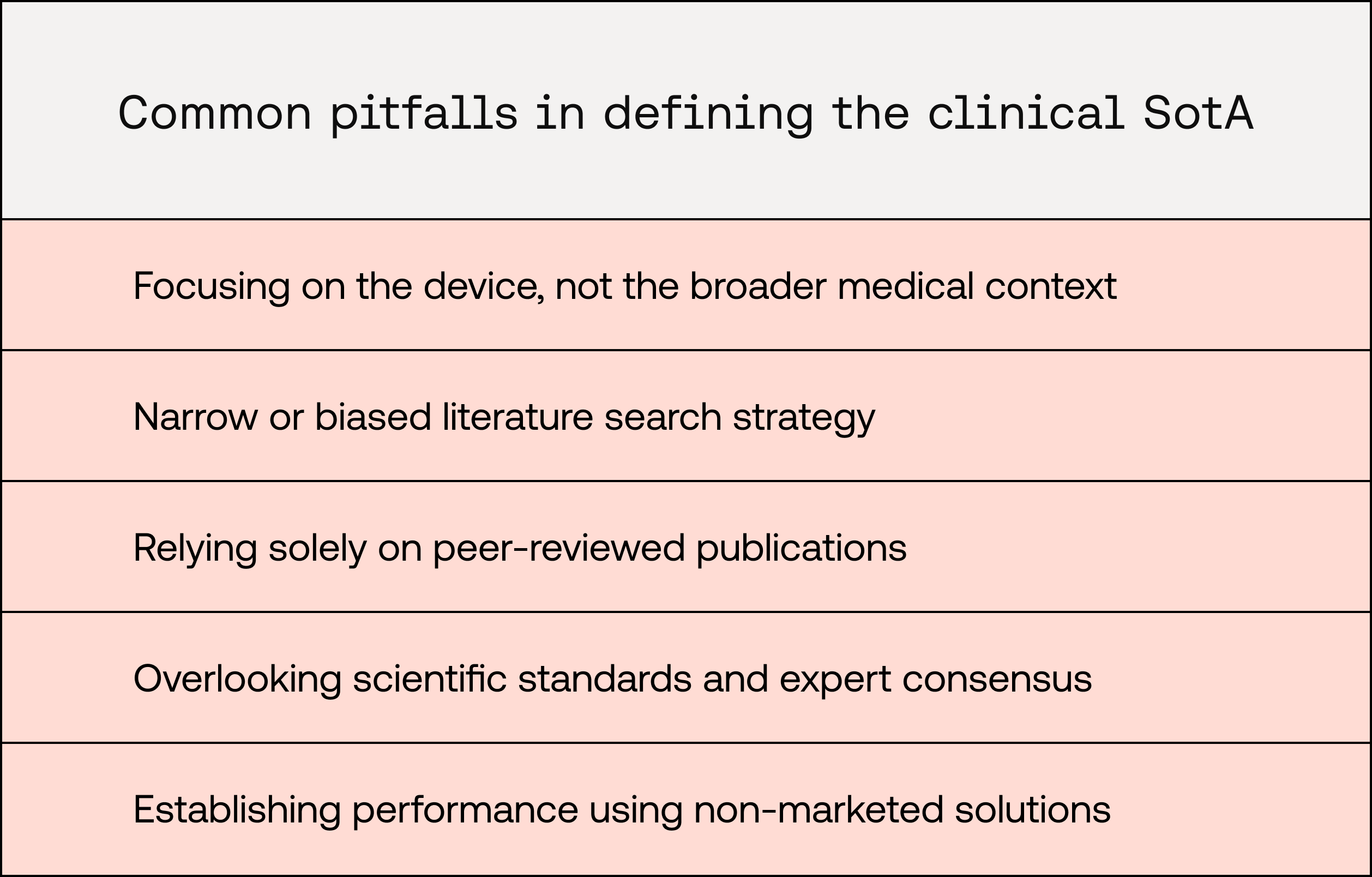

Common pitfalls in defining the clinical SotA

Common pitfalls in defining the clinical SotA

Focusing on the device, rather than the broader medical context

Your clinical SotA should address the clinical backdrop of the area your SaMD intends to occupy. This should include an appraisal of information related to:

- The clinical condition being treated, managed, or diagnosed

- Current treatments available

- Alternative treatment pathways

- Similar/comparable devices

- Clinical best practices

Scenario: A manufacturer creates an AI medical device that is a piece of triaging software. When establishing the State of the Art, the manufacturer has conducted literature searches with research questions that focus on other AI triaging software. This ignores the usual clinical process for triaging, which is typically done manually by humans. As such, the manufacturer has not been able to effectively establish the clinical SotA as they have failed to consider commonly used clinical practices for triage.

Focusing solely on the background related to your SaMD will likely result in being unable to establish the clinical SotA.

A narrow or biased literature search strategy

A weak search strategy risks missing key data. Ensure your search includes multiple databases (e.g., PubMed, Embase), is transparently documented, and uses well-defined, but not stringent, inclusion/exclusion criteria.

It is also recommended that several searches, with different search criteria or focus, be applied to retrieve necessary data. Both favourable and unfavourable data should be identified and appraised for their quality and relevance to your device.

Relying solely on peer-reviewed publications

Published studies are only part of the puzzle. Real-world data, grey literature, safety notices, and clinical practice guidelines often reveal insights not captured in clinical research trials — especially for rapidly evolving fields like digital health or AI-driven solutions.

Overlooking scientific standards and expert consensus

Clinical standards (e.g. ISO, NICE, NIH) and consensus documents often define what is “clinically acceptable.” Ignoring them can undermine your clinical and technical performance justifications or risk-benefit analyses.

Establishing performance using non-marketed solutions

Performance requirements cannot be supported by literature from non-marketed devices or solutions. These requirements must be based on clinically established practices or similar marketed medical devices.

Scenario: Building on the previous example, the manufacturer of the AI triage system reports sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 90% as performance benchmarks — based solely on a recently published research paper of a similar topic. However, to meet regulatory expectations, the manufacturer must benchmark their AI model using performance data from similar marketed SaMDs or clinically accepted outcome metrics.

Consider what performance requirements have been used for similar marketed SaMDs and clinical practice — not just what has been covered in the recent scientific literature.

Why does this matter?

An incomplete or poorly constructed clinical SotA can result in delays in your submission and could undermine the credibility of your clinical evaluation. The clinical SotA is used to assess whether your claims are grounded in a clear understanding of current clinical practice.

Here’s what’s at stake:

- Risk of delays or rejections: If your clinical evaluation is insufficiently supported by the SotA, you may face requests for additional data, justifications, or a rework to your clinical evaluation strategy

- Weakened performance claims: Without a strong benchmark, it becomes difficult to show how your device improves upon — or even meets — the standard of care

- Credibility gaps: A one-sided or outdated SotA can signal to reviewers that the evaluation lacks objectivity or rigour, especially in emerging fields where guidance and expectations are still maturing

- Missed opportunities for strategic positioning: A well-crafted SotA doesn’t just satisfy regulatory requirements, it’s also a chance to position your device within a clinically meaningful context, highlighting its relevance and value to patients, clinicians, and the broader healthcare ecosystem

Ultimately, recognising and addressing these common pitfalls will help you demonstrate a comprehensive and balanced State of the Art that reflects the current medical context — laying a solid foundation for clinical evaluation and critical appraisal of evidence.

Want Scarlet news in your inbox?

Sign up to receive updates from Scarlet, including our newsletter containing blog posts, sent straight to you by email.